Source: Tavis Smiley Show

Bob Moses vividly recalls 1964's Freedom Summer in Mississippi. A SNCC leader and co-director of the Council of Federated Organizations, he'd spent four years working on voter registration in the state and played a crucial role in organizing the campaign. He was also instrumental in establishing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party that would challenge the state's all-white DNC delegation in Atlantic City, NJ that fall. The Harlem native later became an impassioned middle school math teacher, in NY and in Tanzania, East Africa, and used the grant he received as a MacArthur Foundation Fellow to create The Algebra Project, a nonprofit that's become a model program for teaching math literacy.

TRANSCRIPT

Tavis: Bob Moses was just 25 when he began his lifelong commitment to civil rights as a field secretary in Mississippi for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, better known as SNCC.

Four years later in 1964, he was the primary architect of the Freedom Summer Project putting his life on the line working for justice in one of the most violent and rabidly segregated states in the nation. He’s prominently featured in the new documentary, “Freedom Summer,” which airs next week right here on PBS.

Moses is also the recipient of a MacArthur Genius grant which he used to start the Algebra Project in Massachusetts, now a nationwide program. We’ll start our conversation tonight, though, looking at a clip from “Freedom Summer” of Bob Moses talking to the media.

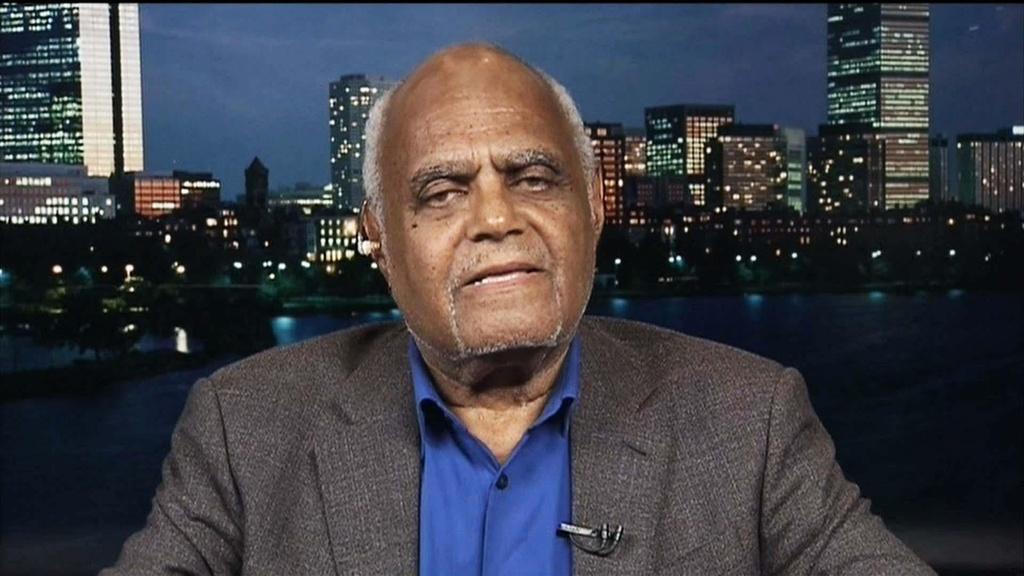

Tavis: Bob Moses joins us now from Boston. Bob Moses, an honor, sir, and I mean that, to have you on this program.

Bob Moses: Thanks, Tavis. I appreciate that.

Tavis: I want to start with a quote from you that, as always, struck me as interesting and fascinating, given that I’m born in Mississippi. “When you’re in Mississippi, the rest of America doesn’t seem real and when you’re out in the rest of America, Mississippi doesn’t seem real.” I think I know what you meant by that, but unpack that for me.

Moses: So actually, Tavis, I think of that as Mississippi during the second constitutional era of this country. I’m thinking of the period after the Civil War right down to the civil rights movement when Mississippi actually established itself as a rule unto itself, as a law unto itself.

You know, they did that in 1875 when the Democrats actually terrorized and murdered Republicans. Now that’s going to be white people murdering and terrorizing Blacks, but you’re really looking at Democrats who were terrorizing Republicans.

And it’s interesting, you know, during that constitutional era, white people in Mississippi were all Democrats and one sign of the shift is that white people in Mississippi are now all Republicans, right?

And it was the movement and actually, you know, Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party that really engineered that shift, that went to the 1964 convention and forced the national Democratic Party structure to get rid of its version of Jim Crow.

Tavis: Let me jump ahead 50 years and then we’ll go back, Bob, ’cause you just gave us such a wonderful history lesson. So 50 years later, we are now celebrating Freedom Summer five decades ago. What do you make of Mississippi and the south today?

Moses: So what I think about it is that Mississippi, for better or worse, became in a sense indistinguishable from the rest of the country. Yes, they may be at the bottom in education. They may be poorer than many other states.

But in terms of being a part of the country, Mississippi is no longer a state which is a rule unto itself, right? And actually, you know, the metaphor for that which is ironic is that in its second constitutional era, there was no FBI office in Mississippi, right? Mississippi was going to send its information to Hoover on its own terms.

So one symbol of it becoming like the rest of the country is the Schwerner, Goodman, Chaney FBI Office. They actually have the names of the three students who were murdered that summer on a big plaque in front of the FBI office in Mississippi.

Tavis: One of the things I find fascinating, Bob – and you know this better than I do – but it’s another sign of the work that you and these other courageous Americans did 50 years ago is that while you’re right about the fact, and I think most point take your point, that back in the day, all the white folk basically in Mississippi were Democrats. Now most of the white folk in Mississippi are Republicans. What’s ironic about…

Moses: 99%.

Tavis: Yeah. What’s ironic about that, though, Bob, is that Mississippi, though, because of the work that you and the others did, it is also the state that has the largest number of African American elected officials.

So here you guys were fighting for the right to help people get registered to vote and now that state boasts more Black elected officials statewide than any state in the union.

Moses: Yeah, yeah. That’s true. And it’s part of the evidence that Mississippi is a part of the country now, right? But, yes, so that’s one of the things that distinguishes what I think of this third constitutional era from the two that preceded it.

Tavis: Yeah. I’m going to talk to Stanley Nelson in just a second here, in a few minutes, in fact, about this wonderful documentary that will be airing on PBS here very shortly. But by way of your own personal story, as I intimated earlier, you become really the leader, the architect, of this Freedom Summer campaign.

But you had been at Harvard previously. You had a master’s degree from Harvard. You were on your way to doing your PhD at Harvard. You had to leave to go take care of your parents and then, from there, you end up leading this campaign.

In short, how did you end up being the man that would help architect this now iconic piece of American history?

Moses: So what happened basically is I just followed my footsteps. When dissidents broke out, I knew that I had to go take a close look at it.

And my Uncle Bill, my father’s older brother, was teaching in Hampton, so I made my first step on my spring break to go down and take a look at what was going on. The students there were demonstrating in Newport News. I walked over with them and then marched on the picket line.

But Wyatt Tee Walker came down to do the mass meeting and he announced that there was going to be an office set up in Harlem. And I got the information and actually went to the organizing meeting for that office and Bayard Rustin was running that meeting and the office. So I started volunteering after school every day.

They had a big event at the 369th Armory where my father was working as a janitor, and Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier headlined that event. Afterwards, I went to Bayard and I said, “Look, I want to go down this summer and work for King.” I thought King was still working in Alabama.

So Bayard sent me to Ella Baker. Ella Baker had the SNCC desk in her office of SCLC and I met Jane Stembridge who was a white volunteer, had been a student at Union Theological Seminary.

And when the coordinating committee came down that summer, Marion Barry was the chairperson. They came down and met and decided – and, mind you, that summer, Barry was going to the conventions, the Democratic and the Republican conventions, to the platform committee, right? They were trying to influence that.

But they decided to hold their first southwide meeting in the fall of 1960 and Jane turned to me and said, “We don’t have any data. We don’t know who did what in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.”

So she and Ella hooked up a tour and I went as a scout for SNCC. And when I hit Cleveland, Mississippi, Amzie Moore who was the head of the NAACP, he was the one that told us what to do. He said, “Look, the students” – he really understood that the students’ sit-in movement was a big, big deal, right?

And he was looking at that energy and he said we need to get that energy here, but not to do direct action and public accommodations. He was sitting on the data that had been beginning to spew out from the ’57 Civil Rights Act about voter registration. So it blew my mind.

I’d been to all these schools, Stuyvesant High School, Hamilton College, Harvard University. No one had ever said anything about the Delta of Mississippi. I’d learned about, you know, the Iron Curtain. I didn’t learn about the Cotton Curtain, so it just blew my mind, right? Here we were.

Tavis: But such a brilliant decision, though, Bob, to involve white and Black students from the north, no less. That was a brilliant decision.

Moses: Yeah. Well, here’s the thing. We had to earn – we were running what I think of now as an earned insurgency. We first had to earn the right to ask the people we were working with, the farmers, the day laborers, the sharecroppers, the domestic workers, to risk really economic and physical violence, even murder, right, to try to register to vote.

Basically, we earned that by getting knocked down and standing back up. You couldn’t earn that by talking, right? When we got knocked down enough and stood back up enough times, I think they thought we were serious. So we earned their participation.

Quiet as it’s kept, we had to earn the right of the Justice Department. You know, the ’57 Civil Rights bill, people poo-poo it, but it actually provided what I think of as the legal crawlspace which allowed us to do the work we did. So Mississippi would lock us up, but the Justice Department really held the jailhouse key.

And as long as we were working on voting, we were able actually to do that work. Then we had to earn the right to call on the rest of the country, right? ‘Cause they were risking their lives, but we had risked ours.

So because we had also risked ours, we earned the right to call on the country to come down and take a look at itself. Black people were not going to be able by themselves to move this country to change what had been in place for 75 years, three-quarters of a century.

Tavis: When you listen to Bob Moses talk – and you’re going to hear a lot more from Bob Moses in this documentary that will be premiering here on PBS June 24 called “Freedom Summer.” In a moment, we’ll talk to Stanley Nelson.

But just to listen to Bob, as you heard a moment ago, just run the names of the list of characters involved in this momentous occasion from King to Belafonte to Ella Baker to Fannie Lou Hamer, so many iconic Americans and I count Bob Moses as one of them.

He is an authentic American hero and I’m honored tonight to have had him on this program to talk about Freedom Summer 50 years later. Bob, I wish I had more time, but I’m going to run to talk to Stanley about this documentary that you are featured in. But thank you for your – seriously, though, thank you -

Moses: Absolutely.

Tavis: For your sacrifice. Thank you for your service. Thank you for your struggle. And thank you for telling the story again tonight.

Moses: All right. Take care, Tavis.

Announcer: For more information on today’s show, visit Tavis Smiley at pbs.org.